Diálogo Latino Cubano

Promoción de la Apertura Política en Cuba

12-03-2018

12-03-2018Who decides the Cuban elections?

The institutionalization of the “revolution” has left Cuba with an electoral bureaucracy that suffocates popular sovereignty, allowing it’s citizens no room for freedom of political expressionPor Leandro Querido

Last Sunday, March 11, Cuba held the second stage of its 2017 - 2018 General Elections. More than 8 million citizens were summoned to elect those to represent in the Assemblies of its 15 Provinces (1,265 delegates) and in the National Assembly of People's Power (605 national legislators).

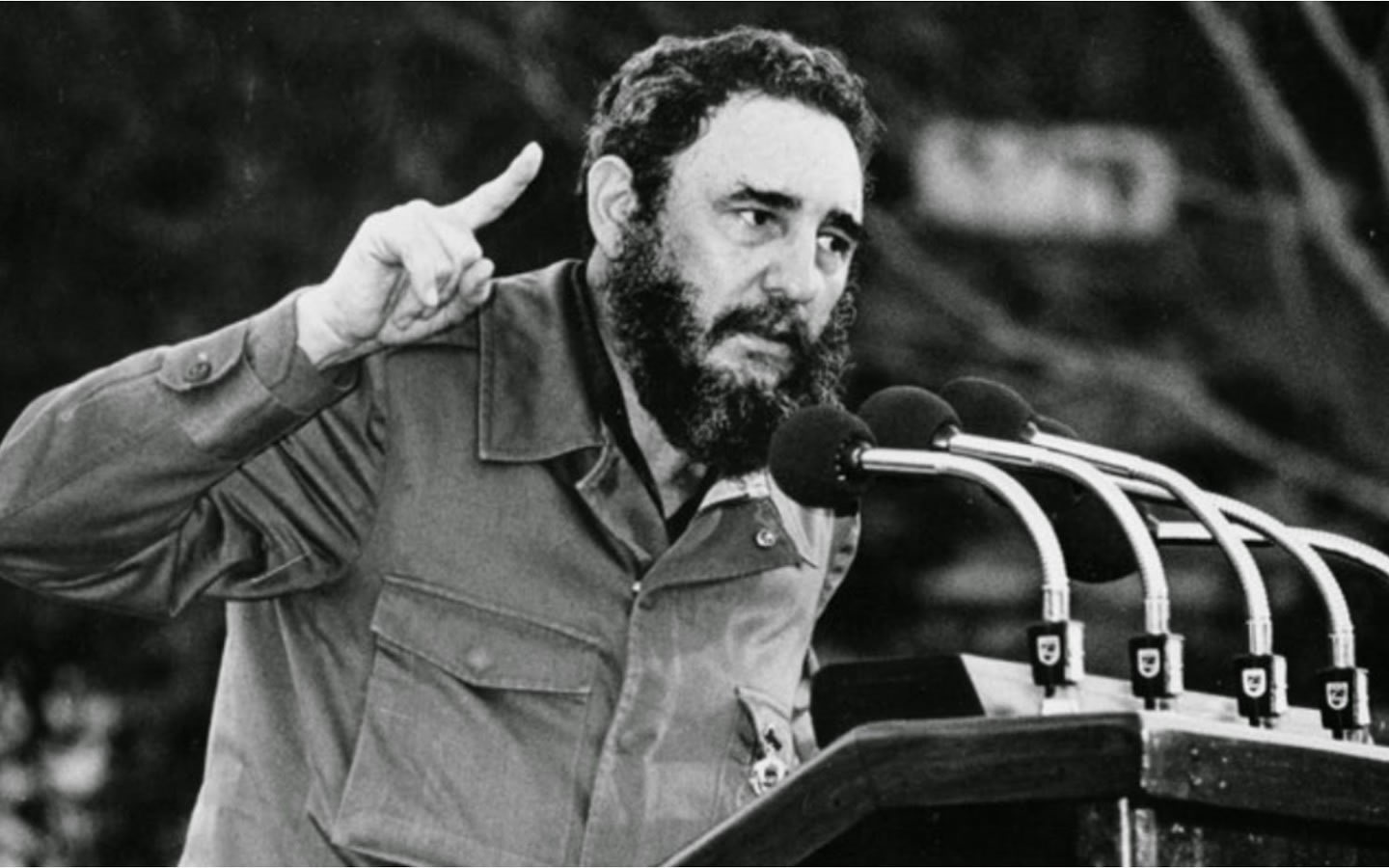

The elections were executed in a highly restrictive manor. One-hundred dissenting pre-candidates have already been excluded in the previous electoral stages and, in the last few weeks, the Cuban government has held arbitrary detentions. There are also some other concerns within the Castro regime. Outside of the country, the free fall of Venezuela seems to have had an effect on various other Cuban interests as well. The commemoration of the fifth anniversary of the death of Hugo Chávez in Caracas exposes the dismantling of a network of regional political support that was once very strong. This also confirms the level of interference by the Cuban government in Venezuela's internal affairs. There are also complications on the home front. Raúl Castro has mentioned that he does not want to continue as the head of government, which only adds to the uncertainty about who will be the future leader of Cuba. The suicide of one of Fidel Castro's sons, who was an advisor to the Council of State, only adds to the rarity of the situation.

Miguel Díaz Canel could be the person appointed to the position that Castro will leave. Díaz Canel is the first vice president of the Councils of State and Ministers of Cuba since February of 2013. Additionally, he is not directly linked to the original revolutionary process as he was born in 1959.

As for the election process, it can be said that it does not differ from previous ones with no glimpse of political openness. It is a great electoral farce in which the opacity and discretion of the intervening institutions distort all notions of legitimate elections.

The organization of the elections is the responsibility of the National Electoral Commission, whose members are chosen, appointed and sworn in by the Council of State. That is to say that all the control of the elections is in the hands of the leaders of the Communist party.

Other evidence of electoral control is linked to the fact that the candidates for the positions for two levels of government, such as the Provincial Assemblies and the National Assembly, are chosen in a procedure carried out by the Candidature Commissions. This commission operates in the different political and administrative levels in which the country is divided: national, provincial and municipal.

The Candidacy Commissions are made up of representatives of the six sectors in which the government has chosen to divide society. This key instance of control is divided between the Central de Trabajadores de Cuba (the Central Workers of Cuba), el Comité de Defensa de la Revolución (the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution), la Federación de Mujeres Cubanas (the Federation of Cuban Women), la Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños (the National Association of Small Farmers), la Federación Estudiantil Universitaria (the University Student Federation) and la Federación de Estudiantes de la Enseñanza Media (the Federation of Students of Secondary Education). This Commission of Nominations is the very negation of pluralism and its function is that of political police to intervene with any candidate that does not corroborate with the interests of the regime.

According to the Electoral Law (1992), at least 50% of the candidates for the 15 Provincial Assemblies and the National Assembly must have come from the Delegates of the 168 Municipal Assemblies. The other half are chosen from citizens who comply with the constitutional and legal requirements to fill these positions. The approval of the candidates for the positions at these two levels of power corresponds to the respective 168 Municipal Assemblies, supposedly after being preselected by the Candidacy Commissions. Therefore, the discretion of the Nominations Committee is ubiquitous and decisive. This is why the Cuban elections are so restrictive.

The first stage of the electoral process passed without any unforeseen events. The authoritarian context of Cuba gives the regime total control of the “assembly” process. It is evident that in this framework the vote, by show of hands, is far from being a democratic example, and is a very effective and coercive tool. A clear example of this occurred in December of last year when the State Council ruled that just over 12 thousand delegates selected at the Municipal Assemblies were to meet in an “extraordinary session.” This session was held to nominate the candidates for delegates to the provincial assemblies of the already deputized National Assembly of the Popular Power (Cuba's legislative parliament). Three days after the order issued by the State Council to the Municipal Delegates, the newspaper Granma announced the names of the 605 candidates for Deputies for the IX period of the National Assembly of People's Power, which were chosen in the Sunday, March 11, 2018 elections.

The second stage of this electoral process has been plagued by institutional abuses. Because of this, the elections that took place last Sunday were neither free nor competitive. The 8.5 million Cubans registered in the Electoral Registry did not elect their 605 Deputies. The process was designed so that voters only endorse what the Candidacy Committee previously chose. Consequently, the members of the Council of State made sure to continue holding power and, therefore, the president.

In short, the institutionalization of the “revolution” has left a process of electoral bureaucracy that suffocates popular sovereignty. Although the semantic intention of the regime strives to highlight its participatory and assembly-like character, it is nothing more than a meticulously plotted simulation.

Stalin once said, “It does not matter how you vote or who votes, where or to whom. The important thing is who counts the votes.” The Castros' electoral system is robust because it not only counts the votes, but also is concerned with how Cubans vote, who votes, where they vote and who they vote for. This machine has worked well for almost 60 years but can no longer hide its deeply undemocratic essence.

Leandro QueridoPolitólogo especializado en observación electoral y director ejecutivo de Transparencia Electoral.

Leandro QueridoPolitólogo especializado en observación electoral y director ejecutivo de Transparencia Electoral.

Last Sunday, March 11, Cuba held the second stage of its 2017 - 2018 General Elections. More than 8 million citizens were summoned to elect those to represent in the Assemblies of its 15 Provinces (1,265 delegates) and in the National Assembly of People's Power (605 national legislators).

The elections were executed in a highly restrictive manor. One-hundred dissenting pre-candidates have already been excluded in the previous electoral stages and, in the last few weeks, the Cuban government has held arbitrary detentions. There are also some other concerns within the Castro regime. Outside of the country, the free fall of Venezuela seems to have had an effect on various other Cuban interests as well. The commemoration of the fifth anniversary of the death of Hugo Chávez in Caracas exposes the dismantling of a network of regional political support that was once very strong. This also confirms the level of interference by the Cuban government in Venezuela's internal affairs. There are also complications on the home front. Raúl Castro has mentioned that he does not want to continue as the head of government, which only adds to the uncertainty about who will be the future leader of Cuba. The suicide of one of Fidel Castro's sons, who was an advisor to the Council of State, only adds to the rarity of the situation.

Miguel Díaz Canel could be the person appointed to the position that Castro will leave. Díaz Canel is the first vice president of the Councils of State and Ministers of Cuba since February of 2013. Additionally, he is not directly linked to the original revolutionary process as he was born in 1959.

As for the election process, it can be said that it does not differ from previous ones with no glimpse of political openness. It is a great electoral farce in which the opacity and discretion of the intervening institutions distort all notions of legitimate elections.

The organization of the elections is the responsibility of the National Electoral Commission, whose members are chosen, appointed and sworn in by the Council of State. That is to say that all the control of the elections is in the hands of the leaders of the Communist party.

Other evidence of electoral control is linked to the fact that the candidates for the positions for two levels of government, such as the Provincial Assemblies and the National Assembly, are chosen in a procedure carried out by the Candidature Commissions. This commission operates in the different political and administrative levels in which the country is divided: national, provincial and municipal.

The Candidacy Commissions are made up of representatives of the six sectors in which the government has chosen to divide society. This key instance of control is divided between the Central de Trabajadores de Cuba (the Central Workers of Cuba), el Comité de Defensa de la Revolución (the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution), la Federación de Mujeres Cubanas (the Federation of Cuban Women), la Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños (the National Association of Small Farmers), la Federación Estudiantil Universitaria (the University Student Federation) and la Federación de Estudiantes de la Enseñanza Media (the Federation of Students of Secondary Education). This Commission of Nominations is the very negation of pluralism and its function is that of political police to intervene with any candidate that does not corroborate with the interests of the regime.

According to the Electoral Law (1992), at least 50% of the candidates for the 15 Provincial Assemblies and the National Assembly must have come from the Delegates of the 168 Municipal Assemblies. The other half are chosen from citizens who comply with the constitutional and legal requirements to fill these positions. The approval of the candidates for the positions at these two levels of power corresponds to the respective 168 Municipal Assemblies, supposedly after being preselected by the Candidacy Commissions. Therefore, the discretion of the Nominations Committee is ubiquitous and decisive. This is why the Cuban elections are so restrictive.

The first stage of the electoral process passed without any unforeseen events. The authoritarian context of Cuba gives the regime total control of the “assembly” process. It is evident that in this framework the vote, by show of hands, is far from being a democratic example, and is a very effective and coercive tool. A clear example of this occurred in December of last year when the State Council ruled that just over 12 thousand delegates selected at the Municipal Assemblies were to meet in an “extraordinary session.” This session was held to nominate the candidates for delegates to the provincial assemblies of the already deputized National Assembly of the Popular Power (Cuba's legislative parliament). Three days after the order issued by the State Council to the Municipal Delegates, the newspaper Granma announced the names of the 605 candidates for Deputies for the IX period of the National Assembly of People's Power, which were chosen in the Sunday, March 11, 2018 elections.

The second stage of this electoral process has been plagued by institutional abuses. Because of this, the elections that took place last Sunday were neither free nor competitive. The 8.5 million Cubans registered in the Electoral Registry did not elect their 605 Deputies. The process was designed so that voters only endorse what the Candidacy Committee previously chose. Consequently, the members of the Council of State made sure to continue holding power and, therefore, the president.

In short, the institutionalization of the “revolution” has left a process of electoral bureaucracy that suffocates popular sovereignty. Although the semantic intention of the regime strives to highlight its participatory and assembly-like character, it is nothing more than a meticulously plotted simulation.

Stalin once said, “It does not matter how you vote or who votes, where or to whom. The important thing is who counts the votes.” The Castros' electoral system is robust because it not only counts the votes, but also is concerned with how Cubans vote, who votes, where they vote and who they vote for. This machine has worked well for almost 60 years but can no longer hide its deeply undemocratic essence.